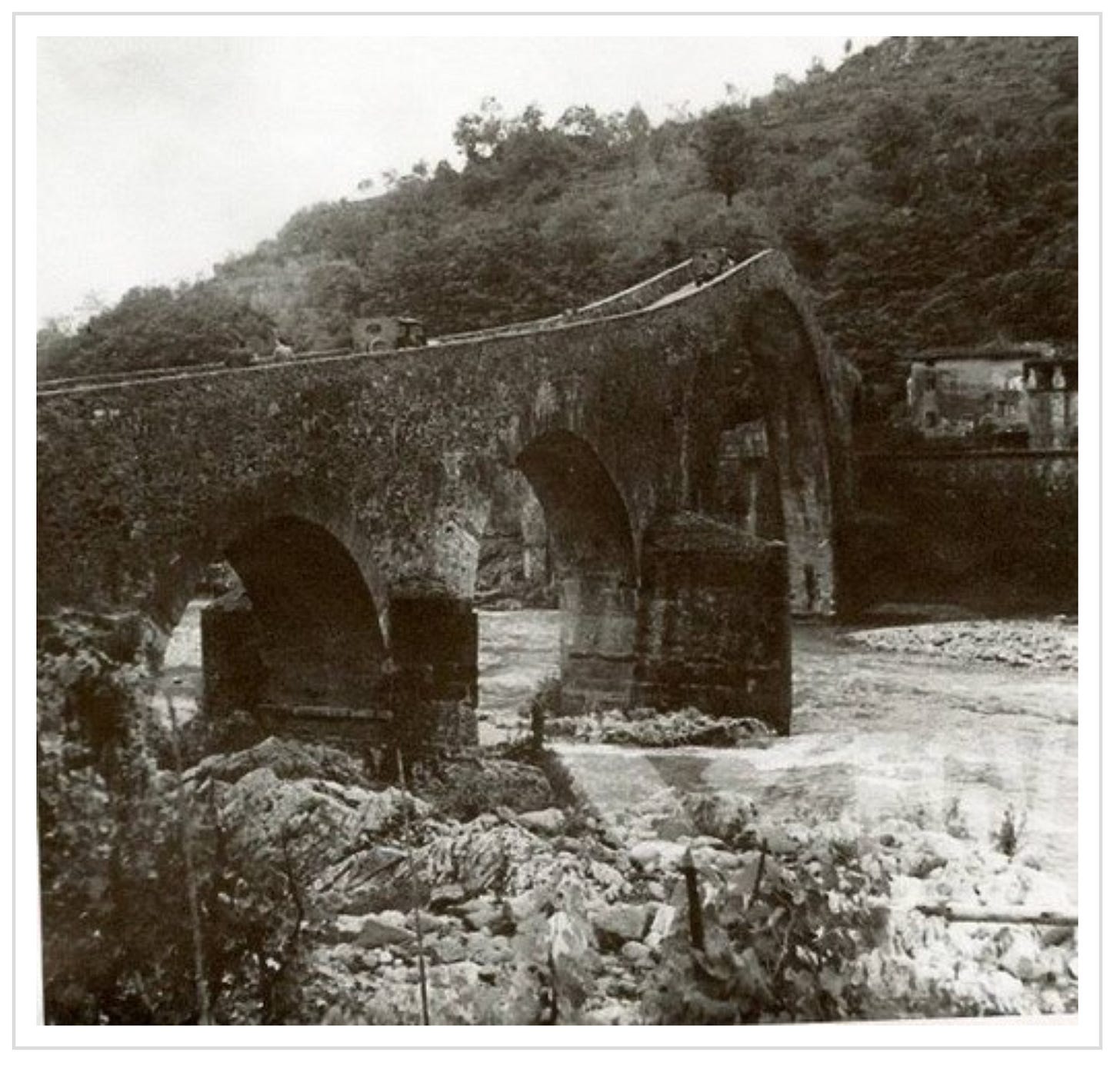

... and there we have it. No, it definitely wasn't possible to just pop a Sherman over the Ponte di Maddalena at Borgo a Mozzano.

At its narrowest point, the 900-year old bridge does measure 2.6m wide – just a bit too tight for the M4 – but there's a jink and a steep wiggle on the Western side that would have definitely prevented a Sherman's tracks from turning cleanly onto the central arch. That said, I can posit a theory as to why the urban myth has prevailed.

This image shows American two jeeps passing over the Devil’s Bridge in 1944. The Italian phrase 'carre armate' – armoured vehicles, or tanks – could (at a push) create some confusion. Tenuous, but it'll do.

With a lot more certainty, the map stories came thick and fast from the town itself today. That’s the reason for being here. Mapping on the Gothic Line.

There was a central administration point for Operation Todt in the town, and plenty of evidence to support the story a young surveyor, Silvano Minucci, volunteered as an administrator in their offices during the spring of 1944.

By virtue of his specialisation, Minucci was assigned to Works Management in the Topographical Survey Office. But as a member of GAP (Gruppi di Azione Patriottica), he was committed to sabotaging the German war effort as much as possible. Every day, he took pieces of carbon-copy paper into work.

Whenever 1:25,000 scale mapping of the areas was taken out of an armoured cabinet, Minucci managed to pull out the carbon-copy paper from its hiding place under his desk, and note down what was being built where: bunkers, anti-aircraft emplacements, communication trenches, and antitank ditches; artillery positions, machine-gun nests, Tobruk-type points, large-calibre howitzers, grids, and – perhaps most importantly – he made notes of the areas from Foce di Colognora to Brancoleria that had been mined.

The idea of mining stretches of an elevated hilltop seems strange, until you see the landscape and understand not only its proximity to Lucca but also the limitations on moving north across this part of the line.

Whether or not Minucci's mapping provided an edge for the Allies, well, that's up for debate. The Americans did find strong resistance at the entrance to the Serchio valley: there’s a peculiar, sharp bottleneck here that sits between Pittone, Castellaccio and Monte dell’Elto. However, when the breakthrough happened in September 1944, it was relatively anticlimactic.

Below, a gratuitous German trench. Another good view, this time from the top of Monte dell’Elto. Rather helpfully, it proved Minucci’s copy-maps were accurate to within about 6 feet. I can also confirm, this was a bramble-laden scramble, and you wouldn’t want to do it in the dark.

Tomorrow, on towards Bologna, following the Gothic Line. More mapping.

what would they have dug that trench with? How long that would have taken through the stone?