Lost in Norfolk - Albert Einstein.

Truth is stranger than fiction. It's a story that's almost lost in time - but for a short while, Albert Einstein hid away on Roughton Heath, in North Norfolk.

A blackboard, a mortar board, chalk dust in the air; intellectual rigour and heavyweight mathematics – this is what we usually associate with Professor Albert Einstein. However, in late 1933, the renowned physicist had his orderly world of academia tipped entirely upside down, depositing him gently for a short while on the North Norfolk coast, in a place that, even today, is a little hard to pin down on the map: Roughton Heath.

Geniuses don’t choose Norfolk by choice. The physicist had been hustled to the heath – to a ‘seaside camp’ – by the British Home Office, intent on shielding him from a very real and terrifying threat: assassination by Nazi agents. For at least six months, Einstein had witnessed a horrifying descent into barbarity in mainland Europe: his theories were being consumed by flames in the public squares of Berlin. In May 1933, an edition of Deutscher Volkswille entitled Jews Are Watching You accused him of “lying atrocity propaganda against Adolf Hitler,” and the caption next to his picture read: ‘Not yet hanged’.

With characteristic moral clarity, Einstein’s forthright condemnation of the Nazi regime and description of its adherents as "beasts in human form," was just a little too loud and too principled for a regime intent on vilifying both his heritage and his ideas. He’d made himself a target. By late March, Einstein had severed his ties with the Prussian Academy; by April, he had relinquished his German passport, eventually seeking precarious safety in Ostend, Belgium – acutely aware of the bullseye on his back

.Under the watchful eyes of local police, a temporary reprieve in a Belgian villa was shattered by a grim dispatch on August 31st. Another intellectual deemed unworthy by the Nazis, Theodor Lessing, had been murdered in Marienbad, Czechoslovakia. The perpetrators, Josef Hackl and Rudolf Max Eckert, left no doubt as to the deadly seriousness of the threat, and Einstein knew his time was running out – but it was at this critical juncture that Lieutenant Commander Oliver Stillingfleet Locker-Lampson, CMG, DSO stepped into the frame as a rather unlikely protector.

A Conservative MP since 1910, and a figure with a rather contradictory past, it’s generally accepted that Locker-Lampson first met Einstein at Oxford, in 1921. He was no ordinary politician. Locker-Lampson’s earlier life was marked by a certain romanticism and a strong anti-communist stance; he’d witnessed the tumultuous events of the Russian Revolution firsthand and, on returning to Britain, had actively campaigned against the perceived threat of Bolshevism, even associating with the more extreme elements of the British right. At one point, he’d even expressed admiration for Hitler, but the stark reality of Nazi persecution, book burnings, and the systematic oppression of Jewish people triggered a profound moral awakening in him. By 1933 though, Locker-Lampson’s initial, naive, views on the Nazi movement had undergone a dramatic and complete reversal, being replaced by a fierce condemnation of their brutality.

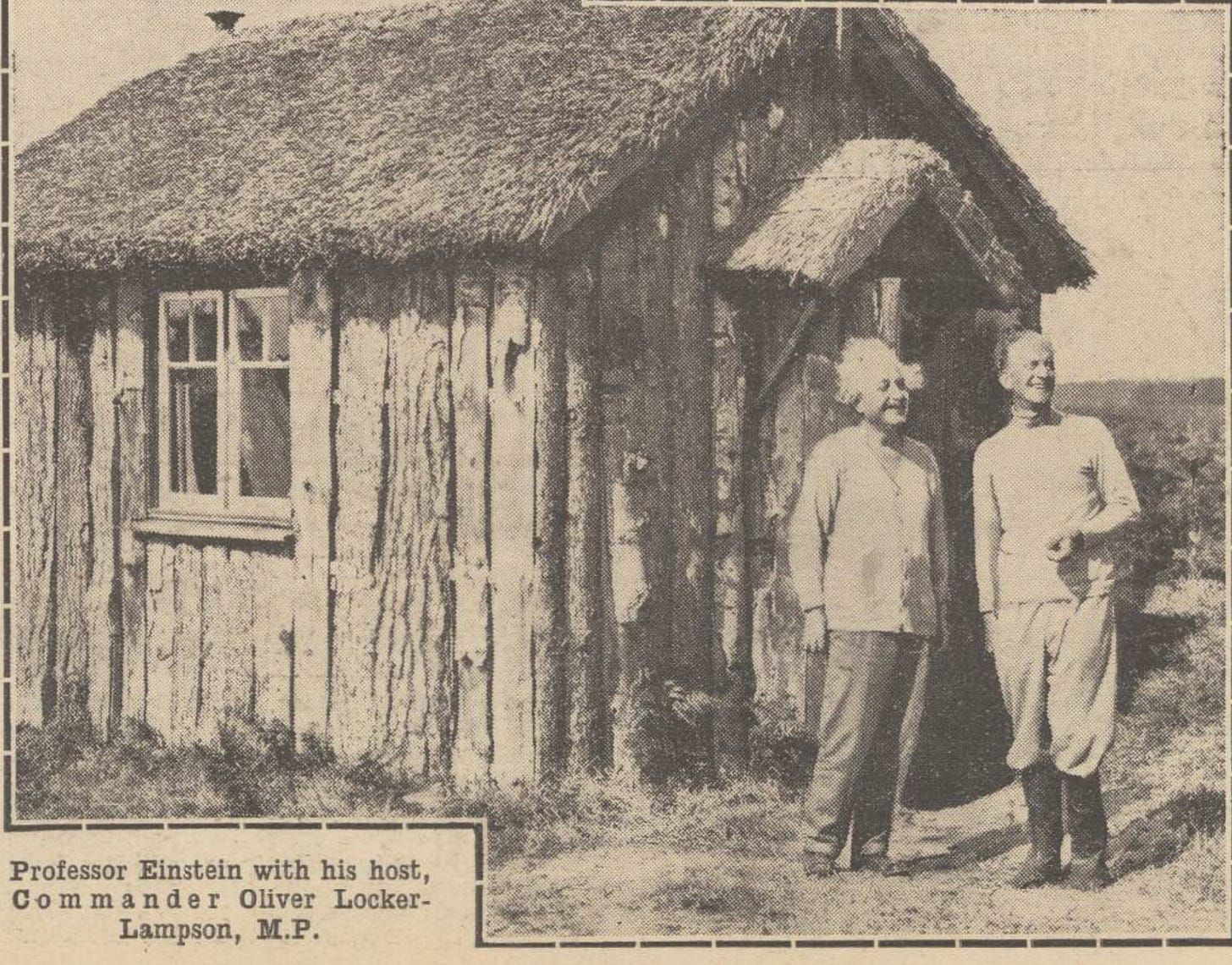

In a powerful display of changed convictions, Locker-Lampson rose in the House of Commons to champion the cause of Jewish refugees. His imposing six-foot-three frame commanded attention; so did his point; and with some light but persuasive lobbying of the Home Office, Locker-Lampson’s plan was set in motion. On September 17th, Einstein and his wife Elsa boarded the SS Albert Ballin, their passage discreetly overseen by two plain-clothes detectives. Conveyed on a low-profile journey from Dover, the physicist finally arrived to hide away at Roughton Heath – Locker-Lampson’s ‘seaside camp,’ not far from his own coastal retreat, Newhaven Court.

Just to be clear, ‘seaside camp’ is a loose description. The stretch of land known as Roughton Heath sits three miles south of Cromer, but finding it on a map today is no simple task - the snippet here is from the early part of the last centurty. Part one side of the main road, part the other; sometimes not mentioned at all on more up-to-date sheets. In 1933, it was a much broader pightle – that Norfolk version of scrubby reach and paddocked land, edged by hawthorn and overlooked by pines, with the constant whisper of sea-salt in the air. Here, as was typical for the time, small temporary buildings had sprung up – sheds by any other name; cabins with turfed roofs; ramshackle little dwellings. Heath Robinson in nature, far more homely on the inside than their outside ever suggested.

The wealth of Locker-Lampson’s political, literary and society connections meant a prominent circle friends visited regularly, but Locker-Lampson had offered the same rustic ‘retreat’ to other men of note: followed.Sir Ernest Shackleton wrote The Heart of the Antarctic while enjoying the best of North Norfolk’s rural hospitality (and later lived in Sheringham, just down the road); but families without other means would up-sticks and holiday here, for several days at a time.

Rustic, yes; but then, if you know North Norfolk at all, you know little houses sit hidden in the hedgerows all over, even now. I used to live in one. And though parts of Roughton Heath seems to have faded over time, it was here that Locker-Lampson took tangible steps to ensure Einstein’s comfort and security. Communal facilities on site included a piano. Marjory Howard and Barbara Goodall - Locker-Lampson’s secretaries - were both armed with .303 rifles, and his gamekeeper, Herbert Eastoe, with a shotgun, took turns in patrolling the campsite. The track to it was, for a while, known as Eastoe’s Loke - you won’t find that on the map, though.

From mid-September through to early October, Einstein enjoyed a measure of peace and tranquillity. Hidden away in a makeshift study; a paraffin stove; a single window offering a view of untamed gorse; notepaper; a borrowed typewriter; a gramophone; long solitary walks around the heath, and brief encounters with a small flock of nanny goats – apparently, he enjoyed their milk. And yet, despite Locker-Lampson’s declared intentions of seclusion and security, Einstein's presence in Norfolk did attract attention.

On the one hand, Locker-Lampson made overtures about the great man’s need for solitude and secrecy, announcing that he would receive no fellow scientists as visitors, nor attend any public functions – but Locker-Lampson also invited the great and the good of Britain’s press-pack to the ‘hideout,’ keen to keep Einstein’s plight in the news.

The Observer’s reporter noted, “England is not a very good place to hide in. Dr Einstein, who has come here to escape Nazi persecution, finds his wooden hut photographed in the papers, with full indications of locality, and Cromer Council considers the question of presenting an address. Germany, I suppose, is presumed to be looking the other way.”

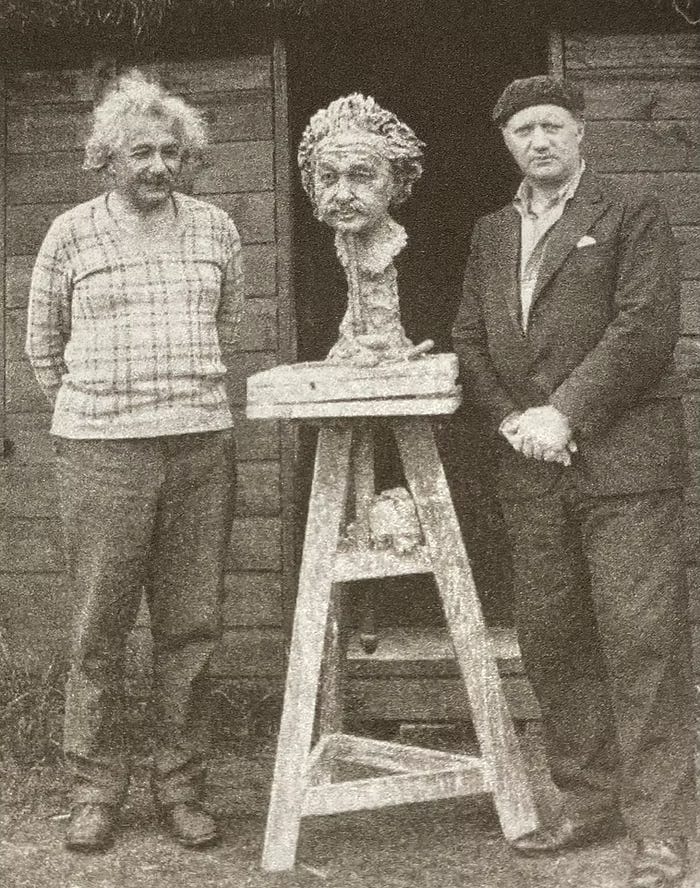

The sculptor, Jacob Epstein, arrived on September 24th. Syndicated newspapers carried the story: “Asked as to what use the bust would be put, the sculptor said no plans had been made at present. Each morning the Professor gives Mr. Epstein a sitting at the Locker-Lampson camp. In the afternoons, the professor resumes his quiet camp life.” That bust would eventually grace the halls of the Tate Gallery.

By the latter part of 1933, Locker-Lampson’s earlier political leanings were firmly in the past, his focus now resolutely on aiding those fleeing persecution. On October 3rd, Einstein travelled with him on the train from Cromer to London – both travelling third-class – to address a gathering of 10,000 people at the Royal Albert Hall in London, a benefit concert for the Refugee Assistance Fund. His voice, perhaps carrying a hint of the anxieties he had endured, was steady and resolute as he urged support for Jewish refugees and a firm stand against the tyranny unfolding in Germany. And then on October 7th, Einstein boarded the SS Westmoreland in Southampton, marking his permanent departure from Europe. He never looked back.

Today, Roughton Heath is a non-descript patch on the map sheet; a caravan park to the west and grassy fields to the east. The wooden huts are long gone, replaced by open space where people walk their dogs. Reports of a large black cat are not exaggerated, but that’s another story.

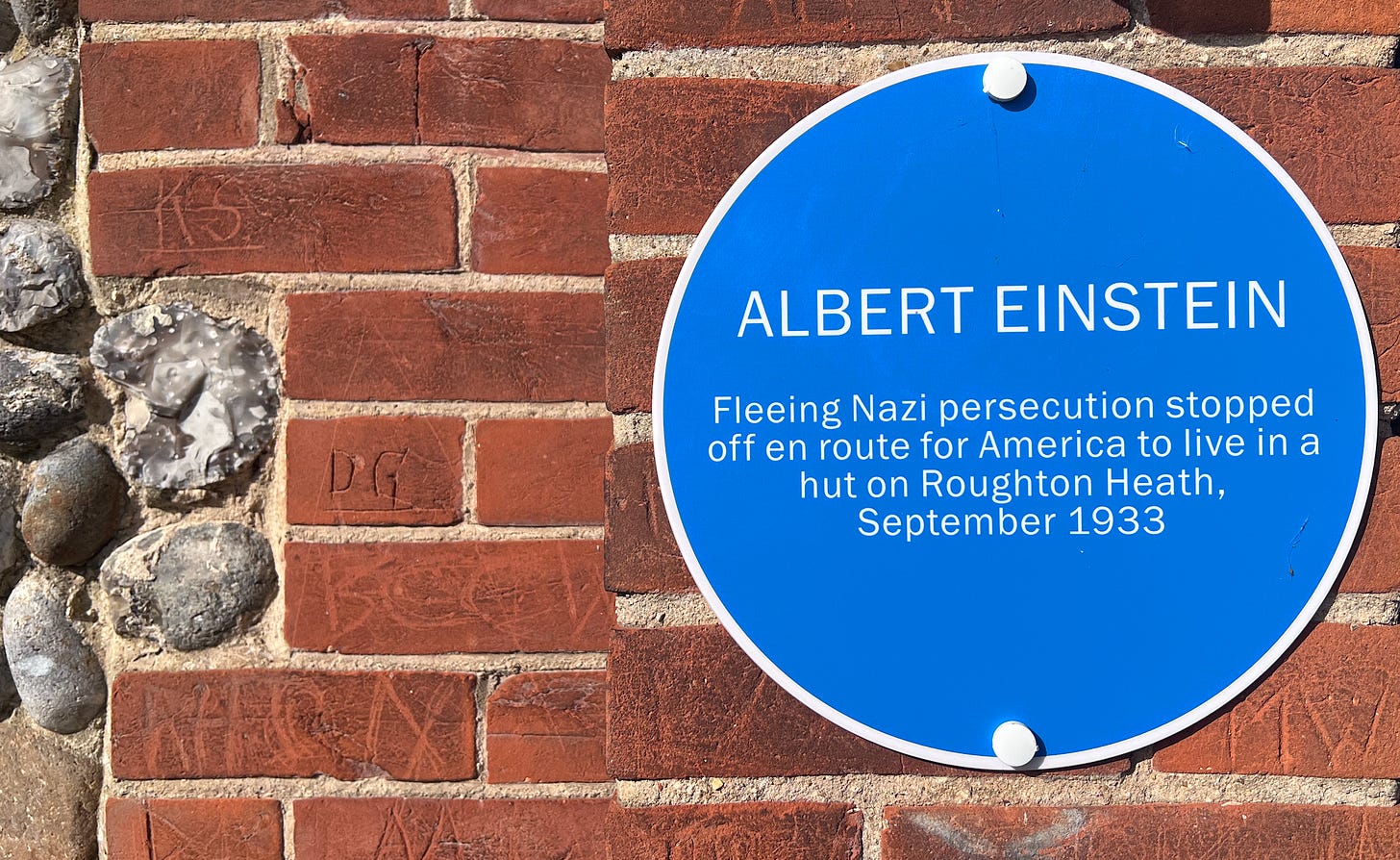

The village of Roughton itself is barely a sneeze. A large hamlet on the way from Cromer to Aylsham; a crossroads between Felbrigg and Thorpe Market - and yet large enough for a pub, of course. Next to the front door of The New Inn (which also happens to be the back door), there’s a small blue plaque.

The story of Einstein’s time in Norfolk might sound improbable, but it is true; much like Roughton Heath: hard to place, hard to define, yet undeniably real.

Absolutely astonishing! Thank you.

Definitely worth reading, many thanks. In 1976 we holidayed in a cottage in Northrepps owned by the Gurney estate, the family were Quakers. I wonder if this additional link helped boost the security for Einstein?