Finding Studley Constable

In which the work of mapping history begins not so very far from home.

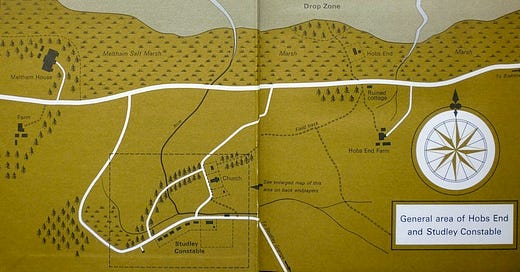

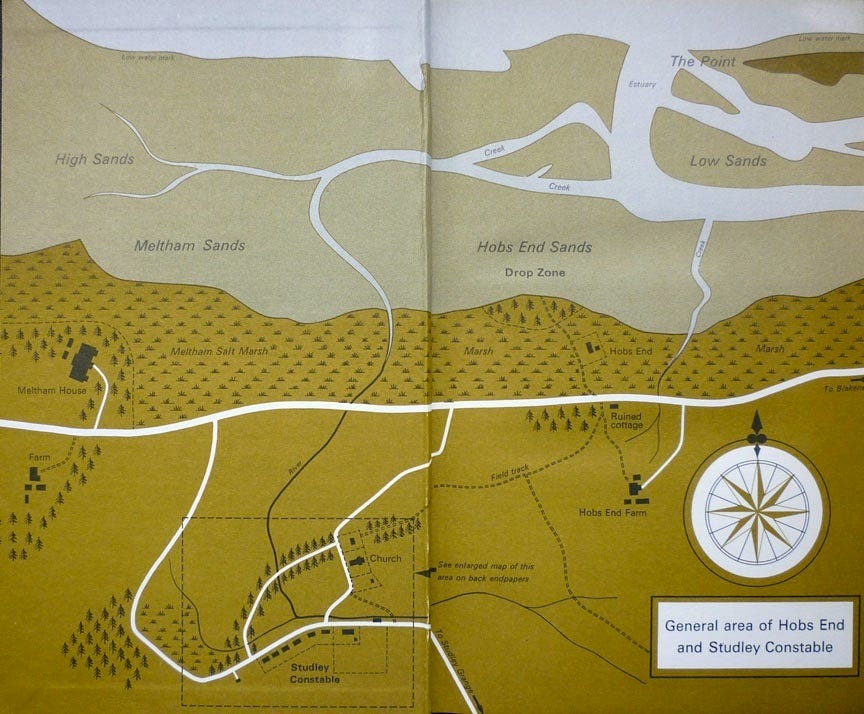

Some maps make more sense than others. Some maps shouldn’t exist, but they do. As moss-tinted endpapers in the book, The Eagle Has Landed, this simple double-page spread does a sterling job of putting one small Norfolk village into context on a map. Famously or infamously, this is an English county that makes life hard for those who want to find it.

There are no motorways. The road isn't straight from one bend to the next. And while the 212-mile journey from London to Paris takes about two and a half hours, it takes almost as long to travel 100 miles - by train - from London to our cathedral city, Norwich. Our highest seat of learning, the University of East Anglia, broke the academic mould when it adapted and then adopted the light-hearted but meaningful 'we do things diff'runt' as its motto - and we all do our best to succeed in that regard.

A long line of daughters talk about the modern historiography that’s been made possible by Julian of Norwich, the first woman to write a book, in or around 1390. Modern, notable, wit-wise sons of the county include Stephen Fry, Charlie Higson, and Paul Whitehouse. The boy Nelson did well; the boy Bowie brought notoriety to the Broads, and the noted heart-throb, Alan Partridge, is more than a local hero - he's a legend in his own lunch break. We all tune in, at some point in our lives, to hear the latest news from Radio North Norfolk: this is anything but Lake Wobegon but our women are strong, some of our men think they're good-looking, and you know what they say about our children - can't read, can't wroi'e, bu' as lorng as theyve orl got six fingurs on the wheel, they ken shoorly droive a tractuh.

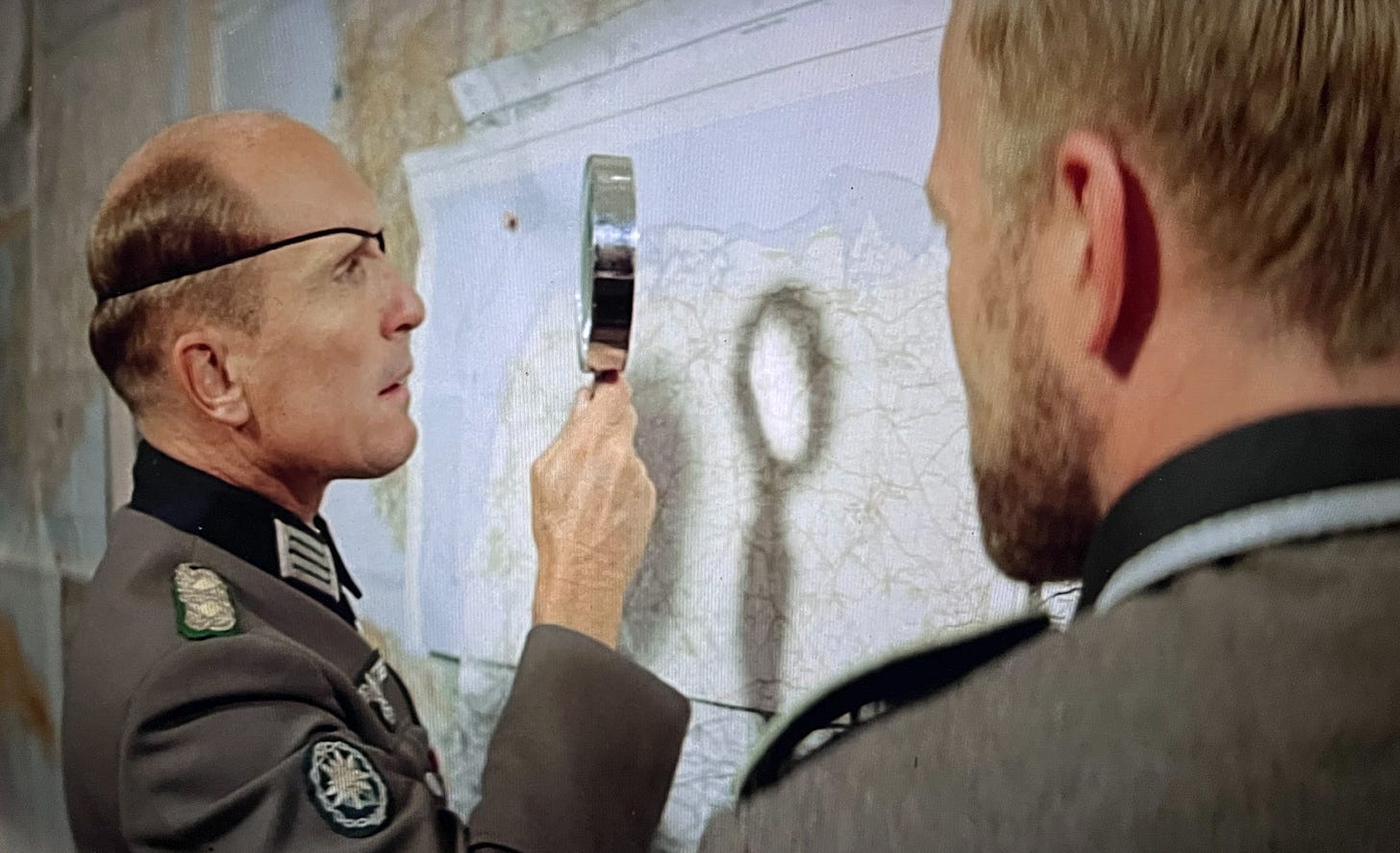

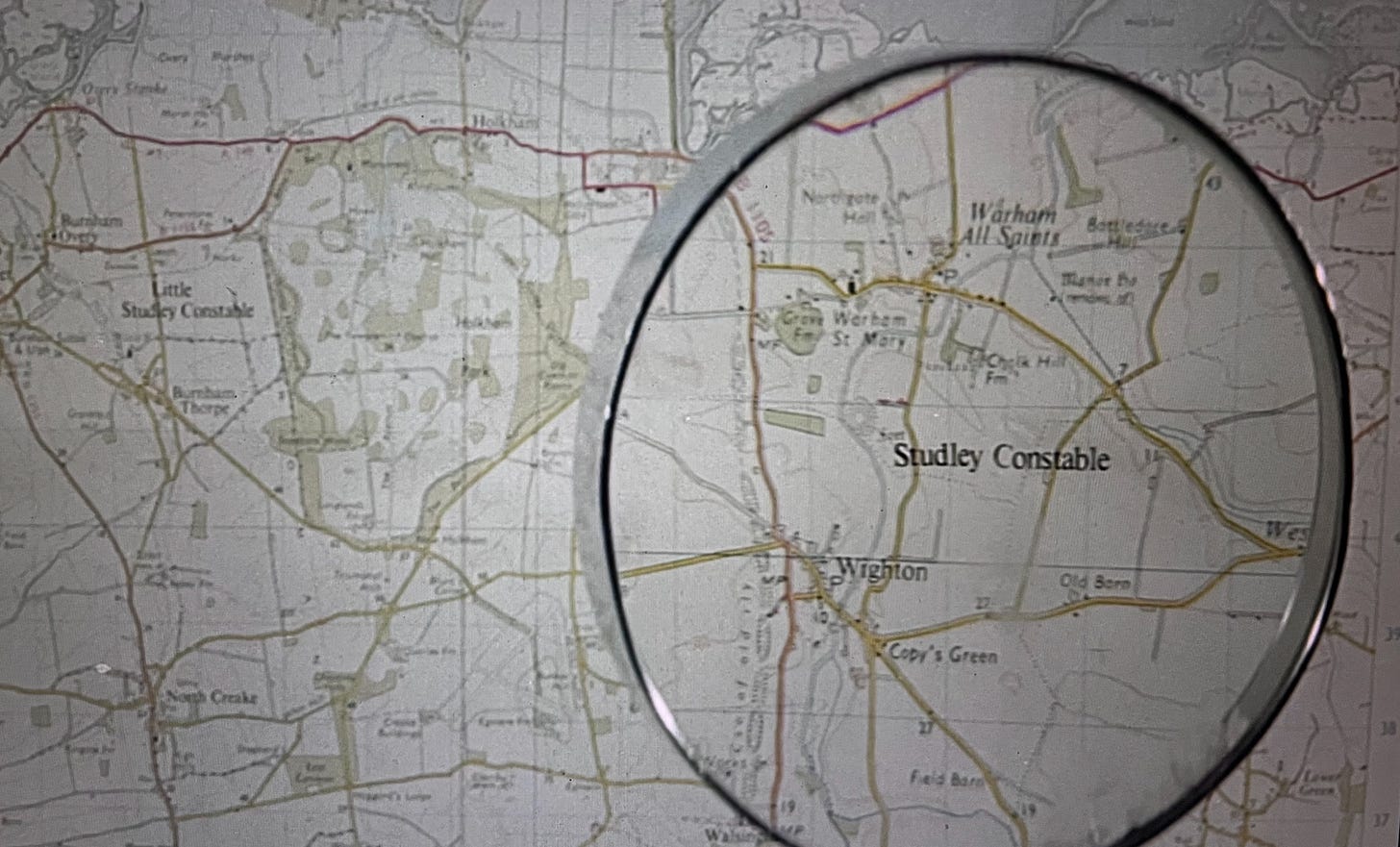

However, if the tourists are travelling in the opposite direction, then a 20-minute drive from my front door puts you smack, bang in the middle of the Warham-Wighton-Westgate triangle (all three hamlets are conspicuous by their absence on the map above), where, on a small number of sheets printed by GSGS in 1943, you will find one village’s name picked out in a particularly sharp black font. This is where my fascination with maps and the Second World War began, with the bizarre notion of Nazi officers finding (or not finding) Studley Constable.

The village itself was first imagined into existence by Henry Patterson (better known as Jack Higgins), and then given more prominence in the 151-minute long film epic, The Eagle Has Landed. A quaint little village for a grand conceit. Many visitors drive through it now, completely unawares, visiting first by accident and then, when they cannot find it on the way home, questioning whether or not it existed in the first place. Or that's how the story goes.

Patterson said it was a tale about ‘good men fighting for rotten causes’. He wrote his masterpiece long-hand - working through the night with a meal of champagne and bacon-and-eggs for breakfast - and surmised that 50 per cent or more of the book was fact: readers must decide for themselves, how much of the plot to kidnap Winston Churchill was fiction.

Perhaps I should have said it was mostly a grand conceit. Churchill did spend plenty of time in Norfolk, before the First and then during the Second World War. At Weybourne Hope, at Overstrand, and - who knows - perhaps at Studley Constable. Real or not, the location is no more than a couple of miles inland from a narrow stretch of the coastline that's always been at risk of invasion, especially where there's deep water close to the shore.

The sea is well-behaved here and while the wind may whistle bitterly along the reach, come midnight there's little or no noise other than tired waves, tinny clanks, and the light gurgle of too-hot-tea being poured into too-small plastic cups. Clear nights tempt hardy locals to wrap up warm for a bit of deep sea fishing from the shingle bank. It’s still water. Good for swimming if you're careful. At it’s calmest, friendly bored seals will pop up, but reminders of a more dangerous time lay all around, and these are fact not fiction.

Between the sea's edge and the coast road leading west to Salthouse, there's an Allan-Williams gun turret, rusting away on its lonesome, communing quietly with the irritated birds that fly in across the marshes from who knows where. To the east, cuboid concrete tank obstacles remain poised and ominous on either side of the road leading into Sheringham - an excellent, waist-high level surface on which to rest your shopping when you've been to the Saturday market. What remains of the tank ditch is less than a shadow, but the dark and empty shells of pill-boxes sit here, there, and everywhere for miles in all directions. Ignore the anachronistic, lone Shilka - the ever-ready ZSU-23-4 - the Soviet self-propelled weapon system standing guard at the entrance to Weybourne's Anti-Aircraft Training Camp on the outskirts of the village. If you're a tourist, and you travel this stretch of road too quickly in your haste to reach Burnham-on-Marylebone-on-Sea, then yes, you're not wrong, it really does do a fleeting impression of a tank as you come round that bend - and this is all normal for Norfolk.

In peacetime and at war, history comes to life on the map. There’ll be more about the maps and the mapmakers soon, and a little extra Studley Constable later. For now, it's late and the seals are calling…

I'm frustrated that my house is precisely under the rim of the magnifying glass so I can't see if it exists or not... but delighted to discover there's also a Little Studley Constable on one of my big circular walks that I think is not in the book or the film other than on this map!

Thanks! Now I want to read Graham Greene's 'The Lieutenant Died Last' and watch 'Went the day well?'